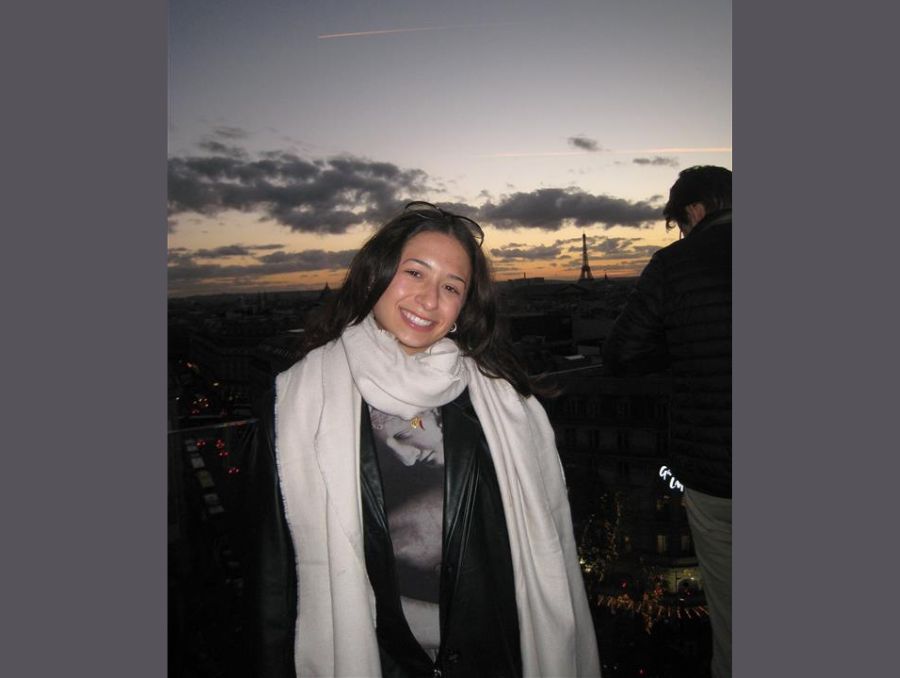

True to the multidisciplinary nature of her work, and true also to a humble personality that often would rather see others praised for their contributions first, Sarah Cowie sees her latest individual honor as a reflection of the help she's received from colleagues and students, and from the trust she's earned from the communities and stakeholders she views as partners.

Cowie, an assistant professor in the Department of Anthropology, learned earlier this month she has been selected as a Kavli Fellow by the National Academy of Sciences. She will participate in the Academy's fifteenth Japanese-American Kavli Frontiers of Science symposium on Dec. 1-4 in Irvine, Calif.

The symposium series is the Academy's premiere activity for distinguished young scientists. The symposia are designed to provide an overview of advances and opportunities in a wide-ranging set of disciplines and to also provide an opportunity for the future leaders of science to build a network with their colleagues. Kavli Fellows are selected by a committee of National Academy of Science members from among young researchers who have already made recognized contributions to science, including recipients of major national fellowships and awards. Since its inception in 1989, more than 175 Kavli Fellows have been elected to the National Academy of Sciences and 10 have been awarded Nobel Prizes.

For Cowie, this latest honor is a continuation of a string of important professional milestones and recognitions she has received in 2016. In February, Cowie was named one of the 105 Presidential Early Career Award recipients for scientists and engineers by President Barack Obama.

"This has certainly been the most exciting year of my career, but to receive individual recognitions for doing collaborative work is very humbling," said Cowie, who has been at the University since 2011. "In some ways it feels not quite right, because I never would have been recognized without the important work and ideas many people shared with me."

Cowie's most recent research, which has focused on an archeological study of the historic site of Stewart Indian School in Carson City, provides vivid illustration of how Cowie seeks out multidisciplinary approaches to make discoveries, and, perhaps even more importantly, in developing productive relationships with key stakeholder groups.

Her work at the site of Stewart Indian School, a 110-acre area of some 50 buildings, has brought welcome resources, research and attention to the old government-supported boarding school in which young Native American students from throughout the region and the country were forced to attend. Stewart, which operated from 1890-1980, has a complicated history and has provided a collaborative backdrop for the local Native American community and a talented researcher like Cowie to learn more about indigenous heritage, as well as supplying a model for future indigenous archaeological efforts throughout the country.

As her research has been recognized on the national stage, Cowie has also been lauded by community stakeholders for her perceptive, inclusive and empathetic manner.

"We've been so fortunate to have proponents and supporters like Dr. Cowie," said Sherry Rupert, executive director of the Nevada Indian Commission, which partnered with Cowie in the effort to bring research, understanding and awareness to the Stewart Indian School story. "For Dr. Cowie to come at the very beginning of the process and speak not only with the Nevada Indian Commission but with the (local Native American) community about this project and what it would entail, and getting everybody's input on that ... having this from the very beginning was so needed. I really love the collaborative spirit that Dr. Cowie showed with her work at the Stewart Indian School."

Cowie's research - with the help of students and Anthropology Department colleagues - is so far-reaching in its scope that it's hard to find any academic discipline that it does not touch at some point.

Although the focus is decidedly scientific and utilizes the most sophisticated technological tools associated with the sciences, there is no question that Cowie's work is grounded just as firmly in the humanities.

"Collaborative archaeology projects like mine can only be accomplished by engaging with diverse colleagues, students, industry, and community members with widespread expertise," Cowie said. "For example, in our archaeological study of Stewart Indian School, our team drew on research from biology to identity plant and animal remains, geochemistry to study the soil, GIS to map our data, history from archives and Native elders' stories, sociology and philosophy to understand power dynamics, linguistics to interpret differing discourses about heritage, political science to discuss heritage policy, and more. Anthropology is a discipline that studies humanity, so we are fortunate to study anything and everything connected to humans."

Cowie, who firmly believes that the first step in any productive research project is to "talk to a lot of people," said that she is regularly energized and inspired by the accomplishments of her colleagues in Anthropology. The department over the past couple of years has seen several other professors earn national renown.

"So many of my colleagues in Anthropology are winning awards and publishing influential work that is getting recognition," Cowie said. "I'm inspired by the fact that my colleagues study various aspects of humanity all over the world. In my early career as an archaeologist, I was focused exclusively on the past. Now, talking with my colleagues and working with the public inspires me to find the value of archaeology in better understanding people's present-day challenges and goals."

Cowie was quick to praise many who have helped advance the goals and specific projects of her research agenda, including the Nevada State Historic Preservation Office, Washoe Tribal Historic Preservation Office, the Nevada Indian Commission, numerous tribal members who shared time and insights, as well as faculty from across the University, the Desert Research Institute, the Nevada Advanced Autonomous Systems Innovation Center, Special Collections in the Library and the Gender, Race and Identity program.

University faculty, in particular, have been "generous in brainstorming ideas with me and teaching my students skills and interpretive frameworks to explore in our own work," Cowie said.

Cowie said she is excited about December's gathering of Kavli Fellows.

True to her nature, she said the multidisciplinary format of the three-day symposium, "requires all participants to discuss research far removed from their specific expertise. I'm looking forward to the challenge, and it's in keeping with how I usually spend time at conferences anyway. I like attending discussions outside my own area of expertise."

The wheels, in fact, are already turning for Cowie as she looks at how the Kavli symposium could help inform her future research.

"It's intriguing to see important work elsewhere that could be applied in archaeology and vice-versa," she said. "For example, one of the Kavli sessions is on epidemiology, and one of my interests is the archaeological study of emergent modern medicine and social inequalities that surrounded it. "So it will be interesting to see how our work could be related."